June 2018

24-hour drinking water for more than 300,000 Nairobi residents will soon become a reality, thanks to the prioritisation of water projects by the Kenyan government. flow’s Clarissa Dann reports on how structured export financing of the Ruiru II dam is making a vital contribution

In a rural village just outside Nairobi, Kenya, Sabina no longer has to make the long walk to collect water for breakfast, bathing and cleaning, as well as crop irrigation. Thanks to a loan from a water NGO, she financed a rain catchment system to store enough water from the rains for her home and small farm. Income from crop sales is helping her fund repayments.

While this has clearly brought a smile to Sabina’s face, she does not have drinking water on tap, and it does not change the wider problem for Kenya’s 46 million inhabitants, 41% of whom still, according to water.org, “rely on unimproved water sources, such as ponds, shallow wells and rivers, while 59% of Kenyans use unimproved sanitation solutions”. Urban slums and rural areas are particularly deprived, with only nine of 55 public service providers in Kenya providing a continual water supply.1

Simon Sayer

Global Head of Structured Trade and Export Finance | Deutsche Bank

Nairobi is inadequately served by four water sources outside the city. The Sasumua, Ruiru I and Thika dams and the Kikuyu Springs cannot meet demand, as recharge capacity has been decreasing and water gets lost in transit as a result of excessive abstraction along the transmission pipelines, pressure losses and illegal connections.2

And this is affecting Kenya’s economic potential.Barrier to economic growth

Kenya, says the World Bank, is East Africa’s largest and most diversified economy, with an ambitious vision of becoming a middle-income country and lifting millions out of poverty in the next decade. As a major communications and logistics hub, with a significant Indian Ocean port and strategic country borders with surrounding Ethiopia, South Sudan, Tanzania and Somalia, it has been one of the fastest-growing economies in Sub-Saharan Africa (with GDP growth of 5.8% in 2016). However, lack of water supply infrastructure was noted by the World Bank as one of a number of on-going growth inhibitors.

In 2012, the Athi Water Services Board (AWSB) launched Kenya’s National Water Programme, set up by the Kenyan Ministry of the Environment, Water and Natural Resources as a “blueprint” for Nairobi and satellite towns, to be implemented in five phases from 2012 to 2030. One element of this plan is the Ruiru II project, involving the construction of a 55-metre-high dam, the transfer of untreated water and a purification plan to supply drinking water to more than 300,000 people.

When the finance we arrange enables critical infrastructure expenditure that greatly improves the quality of life of thousands of people, it becomes rewarding beyond measure

Simon Sayer, Deutsche Bank

Scope of the project

In 2012, the AWSB and the Government of the Republic of Kenya moved water projects to the top of the priority list and various memoranda of undertakings were signed between 2012 and 2015. One of them was for the design and build of the Ruiru II Dam project, for which a consortium was formed between French construction exporters Sogea Satom, Vinci Construction Grands Projets and Egis Eau. It was at this point that Deutsche Bank became involved in financing discussions at the invitation of Vinci – the contract with the AWSB could not be signed until all the financing was in place.

The four main stages of the project are:

- Site investigation;

- Dam construction (preliminaries and general, embankment, spillway, intake, grouting);

- Pipelines construction; and

- Water treatment plant construction.

The work involves “construction of an earth fill dam located downstream of the confluence of the Bathi and Ruiru rivers”, which allows 40,000m3/day of water to be conveyed to the treatment plant. It also involves “the construction of raw water gravity transmission mains, construction of a water treatment plant at Ndumberi Township, and construction of clear water mains and terminal tanks to supply water to Kiambu and Karuri Towns”.

Structuring the deal

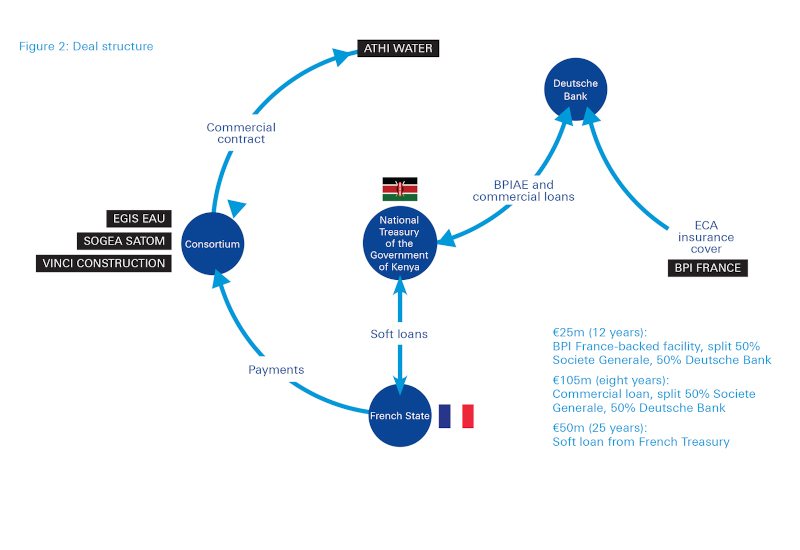

In June 2017, Deutsche Bank arranged a €180m financing for the Kenyan government, acting through its National Treasury for the financing of the engineering, procurement and construction contract signed between the AWSB and the consortium. Deutsche Bank acted as structuring bank, mandated lead arranger (MLA), agent and original lender, with Societe Generale invited to act as co-MLA and co-lender.

Vincent Gabrie, Head of Structured Trade and Export Finance, Paris, at Deutsche Bank, explains that the financing had to “match the terms of the commercial contract” and that “Deutsche Bank keeps a very tight control of the flow of the funds under the contract and receives detailed reporting on what it is being used for”.

9/55

the number of Kenyan public service providers that deliver continual water supplies

Among the positive impacts and outcomes of the deal were:

- Provision of good quality surface water to residents who currently depend on unreliable ground water;

- Distance and time spent in search of water reduced for beneficiaries (especially women and children); and

- Improvements to the standards of living in the region, in particular, in respect of health and hygiene, putting the economy in a better position to increase income and productivity.

This was a complex deal, not least because, while there is on-going good cooperation between France and Kenya, there was only a limited amount of French content, and that determines the size of loan covered by the French export credit agency, BPI France. With a considerable element of local sourcing to clean the site, level the fields and create the dam by moving earth, a substantial commercial loan tranche was needed for €105m (see Figure 2). “Each element of the deal depended on the other – Deutsche Bank and Societe Generale could not sign the deal until the French Government had confirmed the extent of their direct lending to the National Treasury of Kenya,” says Gabrie.

With a large infrastructure project of this kind, says Alarik d’Ornhjelm, Head of Structured Trade and Export Finance, Middle East and Africa, at Deutsche Bank, “we had to extend the maturity of the loans as much as possible – this was a great example of multi-tranche financing and why tapping multiple markets for financing makes sense.” He also points out that with an economy like Kenya’s, where the debt-to-GDP ratio is high (see Key Facts), it was important for the debt to be sustainable. “Kenya has strict concessionality levels of 35% for external borrowing,” says d’Ornhjelm. “So this financing is a perfect example of a sustainable and innovative structure incorporating grant elements and buyer’s credits in order to finance infrastructure development in the African continent.”

Impact and outcomes

“When we support our clients in achieving their export goals, our work is very satisfying. But when the finance we arrange is an enabler for critical infrastructure expenditure that will greatly improve the quality of life of thousands of people, it becomes rewarding beyond measure,” reflects Simon Sayer, Managing Director and Head of Structured Export Finance at Deutsche Bank.

At the time that flow went to press, work was about to start and 24-hour drinking water for the people of Nairobi is set to become a reality in 2020. As Stephane Giraud, Egis project manager, put it when his firm carried out surveys of the project’s engineering structures, “It’s the beginning of a beautiful adventure.”3

Key facts

Kenya

- GDP: US$63.4bn (2015)

- GDP growth: 5.5% (2017), 5% (forecast 2018)

- Public debt % of GDP: 52.5%

- Population: 46.05 million

- Form of state: republic

- Largest trading partner: Uganda (11% exports), China (30% imports)

- Largest export: coffee, tea, cocoa

- Largest import: petroleum, petroleum products

- Strengths: strong GDP growth trajectory, large domestic market, port access, offshore gas fields, horticulture and tourism

- Weaknesses: twin deficits of fiscal and current accounts, political party and ethnic rivalries

Source: Euler Hermes (as at March 2017)

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2GN2E6i at water.org

2 See https://bit.ly/2H8lh88 at nema.go.ke

3 See https://bit.ly/2qhBLRP at egis-group.com